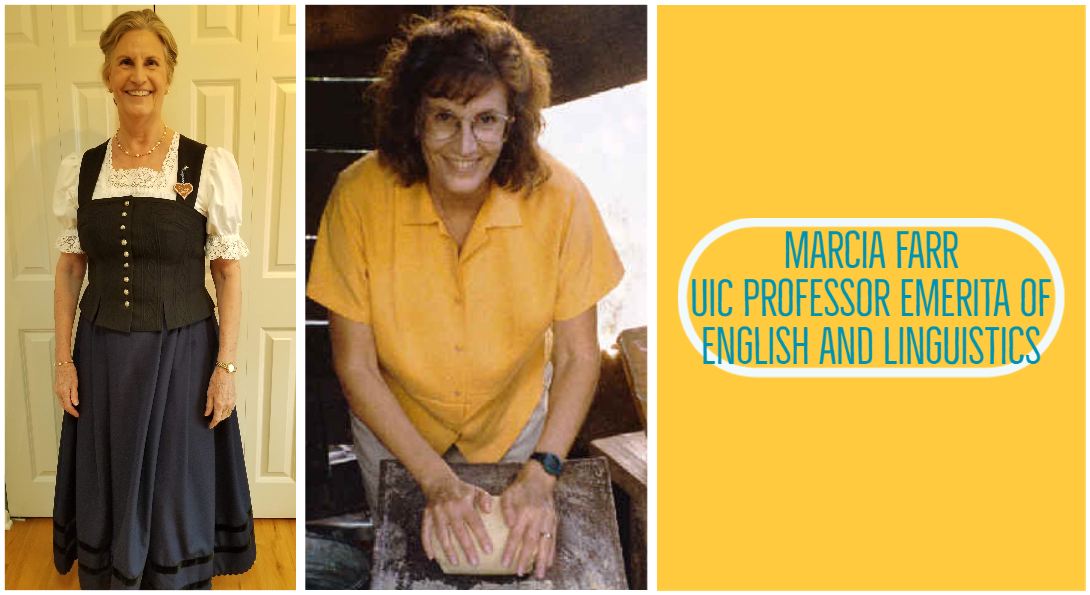

Marcia

Marcia Farr, UIC Professor Emerita of English and Linguistics

As a UIC Professor Emerita of English and Linguistics, my language story is a long one. Growing up in Ohio I studied Latin and French in school, attending Ohio State University French classes as an advanced high school student. At college I studied German “for fun” (my college roommate continues to think this is hilarious), and I subsequently earned a Ph.D. in Linguistics at Georgetown, which included passing an oral exam in French.

In mid-career, as an Associate Professor of English at UIC, I began an ethnographic study of Mexicans in Chicago, most of whom were born in Michoacán, Mexico. This project, of course, required me to learn Spanish, which I did by chatting in the kitchens and living rooms of warm and kind Mexican families, and as a result, my Spanish is closest to my heart (and easiest to generate), after my mother tongue, English. Spanish comes unbidden to my tongue, especially in familial contexts—because I learned it that way. Isn’t language a marvel? I published my ethnography as Rancheros in Chicagoacán: Language and Identity in a Transnational Community, University of Texas, 2006.

Also while at UIC, I directed many doctoral dissertations which explored language and literacy in a variety of Chicago neighborhoods, many of which were multilingual, a fantastic characteristic of Chicago throughout its history (Ethnolinguistic Chicago Language and Literacy in the City’s Neighborhoods, Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004; Latino Language and Literacy in Ethnolinguistic Chicago, 2005). Languages in these studies included Greek, Igbo, Arabic, Swedish, Italian, Lithuanian, Chinese, Japanese, and Spanish, as well as African American Vernacular English and white vernacular Chicagoese.

Later in my career, as I approached retirement, I realized that I didn’t fully know my own ethnolinguistic heritage, assuming I was “white bread,” a mix of English, German, and Irish. I set about researching this and discovered to my surprise that I was actually almost all German (“pumpernickel,” so to speak), a fact which had been unmentioned, and possibly deliberately hidden, in our family. My father, in fact, is 100% German descent, and he is fourth generation on his father’s side and fifth generation on his mother’s side. (My mother is also heavily but not entirely of German descent.)

The signs of German heritage, of course, had been all around me growing up: we ate summer sausage, liverwurst (which we called Braunschweiger), and cheese, and our mother made Lebkuchen and Springerle cookies at Christmas. One grandmother made sauerkraut with pork, and the other grandmother made sauerbraten with handmade noodles. But the only German language left that I could hear was Gesundheit when someone sneezed and once, from my grandfather, Versteht? (Do you understand?).

With all these clues to an ethnolinguistic past, why didn’t we know we were German American? The answer lies in U.S. History, specifically in World War I. My father was born in 1918, the peak year of anti-German hysteria in the U.S. Germany was the enemy, and everything that was German was considered evil. Germans were caricatured as fat, cigar-smoking, and drunken in newspaper cartoons. Germans were arrested and interned in camps, and a German man was hanged to death by a mob in Collinsville, Illinois. The German language was attacked: German books were burned, and German language instruction (both as the medium of instruction and as a foreign language) was legally banned. (Yes, German was the medium of instruction in many Midwest public schools at that time.) German city and street names were changed, as were many German family names. Sauerkraut became Liberty Cabbage. And people stopped speaking German. My family made up a story about John Farr, my great-great- grandfatherand the first Farr to immigrate to the US , being from Wales—but I found his naturalization papers, and he was German.

Is it any surprise that my father did not learn German as a mother tongue, as had his parents, grandparents, and great grandparents (and one set of great, great grandparents), most born in the U.S., before him? Yes, as a FIFTH generation American, my father was the FIRST generation NOT to learn German as his first language. I emphasize this to contrast it with the criticism of Spanish-speaking families today for “not learning English,” when in fact they are learning English over the generations much more quickly than many Germans did 100 years ago.

I end my language story with my current quest. I am learning German again, although I dearly wish I had heard it at home to ease this process. But then again, learning a language is fun for me, struggle though it may be!